South Carolina  SC History

SC History  SC's Turkish People

SC's Turkish People

This article was submitted to SCIWAY by Glen Browder, PhD a native of Sumter County. If you are interested in publishing a piece about South Carolina history, please contact us at service@sciway.net.

South Carolina's Turkish People

By Glen Browder, PhD and Terri Ann Ognibene, PhD

There are many different renditions of fact and legend regarding the Turkish people of Sumter County, South Carolina.

One historian, exercised unusual bluntness for an academician by putting it this way in a publication celebrating the Palmetto State's tri-centennial anniversary:

A stranger visiting Sumter County today may come across a baffling breed called "Turks." In recent years these Turks, known also as "Free Moors," have claimed and received recognition as white citizens. Their status in ante-bellum South Carolina was less clear, and their origin has been the subject of much speculation. So meager are the facts relating to them that the wildest conjectures, based on what must surely be flight of fancy and geographical ignorance, have been advanced to support their origin. (1)

Among those wild conjectures was the fantasized account of Charlestonian Herbert Ravenel Sass. According to Sass, these people may have been descendants of "golden women of the East." He speculated that the Turkish people originated from "slender, raven-haired, golden-skinned creatures," stolen by pirates known as the Red Sea Men from nobles of the Great Mogul's Delhi court, who were on a pilgrimage to Mecca, and brought to South Carolina three centuries ago. (

2)

Almost as curiously and somewhat ironically, Ebony Magazine called the Dalzell group a "raceless" people who distrusted Whites and disliked Blacks. (

3)

Are the Turkish people of Sumter County a "baffling breed" whose origins are cloaked in fanciful ignorance? Are they descendants of "golden-skinned creatures" kidnapped and brought here by pirates? Is their enclave a "raceless" yet racist clan?

Turkish Traditional Narrative and Recorded History

This obscure community of dark-skinned families has always traced its oral history back to an Ottoman refugee who served the colonial cause in the Revolutionary War; and they lived insular, shunned lives in rural Sumter County for many generations. In fact, they had to go to Federal Court to be able to send their children to "White schools" during the 1950s. (

4) Only in the past few decades have they begun to enjoy the full blessings of American life.

A brief version of their traditional narrative – as told by local citizens – held that a "Caucasian of Arab descent," known as Joseph Benenhaley (or Yusef ben Ali, his perhaps Ottoman name), made his way from the Old World to South Carolina and served as a scout for General Thomas Sumter in the American Revolution; and the grateful General had given Benenhaley some land on his plantation to farm and raise a family. A few outsiders married in; but most identified with the ostracized community and their progeny considered themselves as people of Turkish descent. Amazingly, they persevered as an enclosed society-numbering several hundred persons in the Dalzell area at mid-twentieth century – separate from both White and Black South Carolinians. (

5)

Joseph Benenhaley

[Provided by Glen Browder, PhD; Original sketch by artist Charles Marsh of Summerton, SC]

The problem is that the traditional narrative of Joseph Benenhaley and his Turkish descendants has usually been considered no more than myth, a fable concocted to sustain them through unpleasant realities of hard history.

Most early scholars ignored or dismissed the Turkish tale and labeled these people "tri-racial isolates," a mixture of poor White settlers, disassociated Native Americans, and runaway or freed Africans (

6); and other writers disparaged them as "so-called Turks" and a people of low stature. (

7)

For example, almost a century ago an unidentified writer for

The State newspaper painted a dreary, fatalistic picture of this community:

Most conspicuously characteristic of all, however, is their utter lack of spontaneous joy. They wear, one and all, the air of patient and unquestioning acceptance of life as they find it. But what does the future have to promise them? Bits of flotsam from life's ebb-tide, left stranded between two layers of a civilization which provides no place for a third element. Prevented by racial instinct from amalgamation with the Negro; seeing in the future nothing but a continued marriage and intermarriage with those of their own clan, and a repetition of the age-old struggle for existence; they are faced by a problem the solution of which only the future can tell. (8)

Additionally, here is the cryptic, concluding paragraph of a provocative report written by another anonymous observer:

Unobtrusively they go their lonely way. In spite of their Baptist affiliation, their Mohammedan ancestry has stamped then with an utter lack of spontaneous joy. With tragic patience they apparently accept as unalterable their struggle to exist in abject poverty. Fired with no zeal to unite in common endeavor, beset with no adventurous spirit to roam beyond the limited radius in which they have remained since the settling of their earliest progenitors, they remain a submerged and isolated group. It is kismet. (9)

Normally, such characterizations would be considered unacceptable for consideration because of their uncertain authorship, disparaging nature, and lack of supportive documentation; however, these assessments are presented here because they apparently were the sources, thereafter, of many published characterizations – positive and negative – about the Turkish community.

Some contemporary activists have even claimed that these mysterious families are/were Native American Indians. (

10) Several ancestors with Native American links married into the Turkish people in the 1800s; and numerous individuals with surnames associated with the Turkish community now identify with their Indian heritage. These people have disavowed the Turkish narrative and have achieved state recognition as the Sumter Tribe of Cheraw Indians in 2013.

But most Turkish people have persisted in claiming Turkish identity believing their oral history. As one elderly Turkish gentleman, Eleazer Benenhaley, has written: "God knew what He was doing when He created me. . . . I have lived 73 years as being of Turkish descent. I have no desire to be anything else." (

11)

Confirmation of the Turkish People's History

Most recently, exhaustive and comprehensive research has been presented regarding the history of the Turkish community over the past two centuries; and this new research confirmed their traditional narrative. The authors of this manuscript produced thorough documentation of the Turkish settlement in

South Carolina's Turkish People, which was published by the University of South Carolina Press in 2018; and, consequently, the South Carolina Commission for Minority Affairs (which had previously certified the Sumter Tribe of Cheraw Indians) settled this controversy by clarifying the official record regarding the Turkish people. (

12)

The SCCMA's Executive Director issued the following annotation (dated Nov. 26, 2019):

The historical and ethnological backgrounds of numerous dark-complexioned families of Sumter County, SC, have until recently been matters of oral tradition and weak documentation. Some, who considered themselves of Native American ancestry, hailed ties to North Carolina Indians from the Revolutionary War era; and others, who considered themselves of Turkish descent, subscribed to a narrative of an Ottoman patriarch dating back to the same period in Sumter County.

The Native Americans (including some individuals who also were related and associated with the Turkish community) organized themselves as the Sumter Cheraw Indians early in the current century. They believed the Turkish people to be Native Americans who long ago adopted the "Turk moniker" in order to avoid persecution by White authorities. Their application for tribal certification was approved by the SC Commission for Minority Affairs in 2013.

However, new research provided in a recent publication has demonstrated conclusively that the Turkish people of Sumter County originated from patriarch Joseph Benenhaley and constituted a separate, distinct community of their own for most of the past two centuries; and it would be erroneous for anyone to characterize the Turkish people as Native Americans or as part of any Indian Tribe recognized by the South Carolina Commission for Minority Affairs. Persons interested in the story of this group should consult South Carolina's Turkish People (University of South Carolina Press, 2018) by Dr. Terri Ann Ognibene and Dr. Glen Browder.

Therefore, the South Carolina Commission for Minority Affairs hereby acknowledges the history and heritage of the Sumter County Turkish community and adds this annotation to its official files regarding certification of the Sumter Tribe of Cheraw Indians.

The bottom-line, big-picture significance of this annotation is that the South Carolina Commission for Minority Affairs thereby rendered an official and conclusive judgement in favor of the Turkish traditional narrative.

The rest of this paper will present selected documentation of the Turkish people's history.

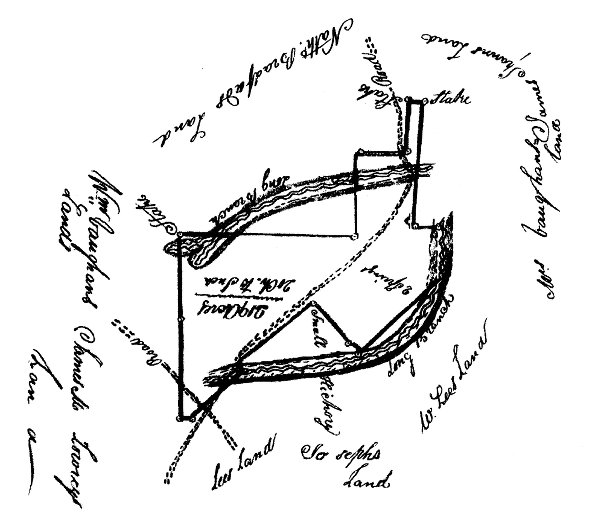

General Sumter's Land Survey

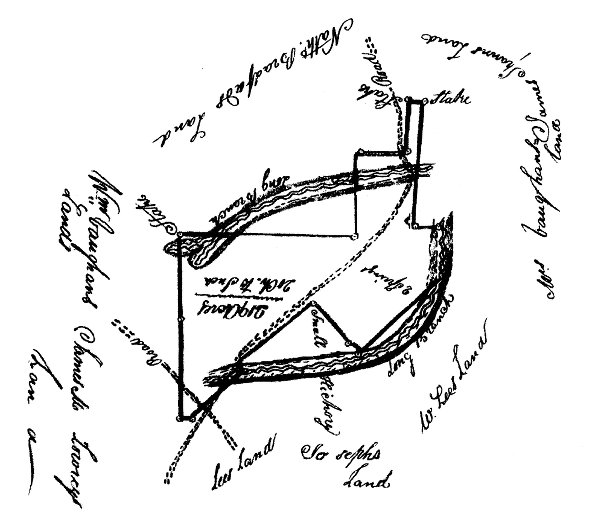

The initial documentation attesting to Turkish oral history was an 1815 land plat of a portion of property belonging to Revolutionary War hero Thomas Sumter (1753-1823). This document, found in the basement of the Sumter County Courthouse, consisted of a survey that was requested and signed by General Sumter; it had "Josephs Land" clearly marked near Long Branch. (

13) Decades after Benenhaley's death, the Sumter County Probate Court described the homestead as "Real Estate of Joseph Bennenhally, deceased, situate in said County on waters of Black River, and containing thirty three acres (33) more or less, originally granted to said Joseph Bennenhally by Thomas Sumter by Deed dated November 1815." (

14)

Excerpt of a survey plat dated 1815 that was requested and signed by General Thomas Sumter, with "Josephs Land" marked in the lower part of the plat

[Provided by Glen Browder, PhD; Courtesy of the Sumter County Office of Mesne Conveyances (Deed Book DD, pp. 35, 36)]

Matilda's Letters

Perhaps the most dramatic testimony to the group's oral narrative was a series of letters written by Matilda Ellison Benenhaley (1842-1936), grand-daughter of South Carolina's largest Black slave-owner, who married into the Turkish community. Matilda was "barren" (as she noted in one of her letters) and, therefore, she never contributed to the Turkish people's bloodline; but, very importantly, she knew the early Benenhaleys and attested to the veracity of the community's traditional narrative. In these letters, which had been passed down from generation to generation, Matilda wrote that the original Benehaley was indeed "an Ottoman," had been "bonded by the Spanish at sea," "kept from freedom in the Indies," but "persevered" and was "made free," served with "General Sumter in the War, who gave him land at "the Home Place near the Branch" after the war." (

15)

Matilda Ellison Benenhaley, circa late 1800s

[Provided by Glen Browder, PhD; Courtesy of Greg Thompson Collection, donated to the collection by Isaac Benenhaley/David Peagler]

Genetics, Genealogy, and Graveyards

The Turkish people have always been extremely skittish about genetic testing, but DNA results for eight direct descendants of the supposed patriarch, Joseph Benenhaley, support the traditional narrative. Although such testing has its problems, several cases from a select group can be useful in combination with other information; and these collective reports complied with hypothetical origins from a Mediterranean/Middle Eastern/North African progenitor, with substantial White European admixture, some evidence of Native American linkages, and no significant Sub-Sahara African contribution. (

16)

Additionally, a genealogical census of 270 Joseph Benenhaley descendants who lived in the Dalzell area during the 1800s provided salient and persuasive patterns. Benenhaleys comprised slightly over half (51%) of the individuals in that group; and six intermarried families – Benenhaleys, Buckners, Hoods, Lowerys, Oxendines, and Rays – accounted for almost all (91%) of the names in that confined community during its formative generations. (

17)

Finally, a survey of graveyards at the two churches (Long Branch Baptist Church and Springbank Baptist Church) that have served as principle places of worship for the Turkish people during the 1900s produced an impressive display of this distinct community's heritage. The survey showed that people who were either born Benenhaleys or married into that "first family" comprised a slight majority (51%) of interred individuals; and the same six family surnames again accounted for virtually all (91%) of the individuals resting-in-peace in those cemeteries. Also, few individuals with Turkish-community names were buried outside the Dalzell area, attesting to the isolation of that group. (

18)

This research demonstrated that the Turkish people did indeed endure as an enclosed ethnic community-originating from Joseph Benenhaley and known as "the Turks" – in rural South Carolina for almost two centuries.

Long Branch Baptist Church Cemetery

[Provided by Glen Browder, PhD]

Oral Interviews

From the Revolution until the dramatic social changes of the 1960s, as throughout most of the South, whites and blacks in Sumter county lived in different areas, attended segregated schools, went to their own churches, and often sat in separated places in theatres and buses. The Turkish people didn't really fit cleanly into this broader black vs. white paradigm. Outside Dalzell, they were always shunned as "the Turks". Somewhat like their black neighbors, they were subject to insults, intimidation, and systemic oppression. (

19)

Usually, they kept to themselves. Most Turkish people of Sumter County have adhered to an ancestral understanding that they are "white people." Their skin color has been described over the years as dark brown, light brown, olive, and tanned; but it is not uncommon, nowadays, for them to be light-skinned with blond hair and blue eyes. Most believe that the original Benenhaley was truthful in declaring his ancestry, but they do not adhere to Old World ways. Their culture mainly reflects their long experience as dark-hued common folk harried by discrimination in rural South Carolina. Their existence has always revolved around the family, their school, their church, their farms, and whatever jobs they could find. (

20)

The Turkish people have always been reluctant to talk with outsiders about experience in Dalzell. As one scholar reported in the 1970s: "The mood of the community strictly opposes any sort of historical investigation. The people will tell any would – be historian that they don't know anything, don't think that anyone else does either, don't see any point in it, and think that he should go talk to some other member of the community." (

21)

However, four elderly individuals – "Boaz," "Helen," "Jean," and "Tonie" (all pseudonyms because feelings still run high in this area) – did share information about their personal lives and community experience; and their common statement as "the Turkish people" is a passionate and moving declaration:

"We are the Turkish people of Sumter County in the state of South Carolina. Our story has never been told fully and accurately. We have roots that extend all the way back to the Revolutionary War, and we fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War and for America in World Wars I and II. However, for two centuries our rich history has been overlooked or misrepresented, our cultural identity has been questioned, and we were denied equal access to education because of the tones of our skin. We persevered; and we prevailed. Now, though our spirit endures, the Turkish community faces new and different challenges, as a fading ethnicity, in the twenty-first century." (

22)

The four participants all stated that they were White people of Turkish descent; and they related their origins to General Sumter having brought their ancestors to Sumter County. Boaz explained his confidence and pride in the traditional narrative this way. "I assume I accepted it just like anyone else who would have been from whatever ethnic background they were from. That's who I am ... and I hold my head high." (

23)

The respondents expressed strong feelings about how Turkish separatism became so entrenched and ugly for so many generations. Boaz speculated that each ethnic group probably just felt more comfortable being with people like themselves: "I don't want to have anything to do with you just as much as you don't want to have anything to do with me." Despite his explanation of mutual disdain, it was clear that Boaz viewed white discrimination as the main cause of the extended, lonely history of this community. He noted, with sadness, that "the Turkish boys and girls were not allowed on teams like the American Legion baseball teams and those types of things. The segregation was almost as bad as the segregation of the Blacks. Not as bad, but bad enough." (

24)

Tonie remembered having to stay out of school for a year during the integration movement. "It was awful," she said. "You never knew what they were going to say to you or what they were going to do to you. Even the teachers were prejudiced. Traumatic. Kids calling you 'Turk,' the bus leaving me and I would have to go back home. I'd have to have an excuse the next day about why I wasn't in school, and I would put, 'The bus driver refused to pick me up.' They didn't care. If they were the only ones on a seat, they would put their books on the other side of the bus so that you couldn't sit there, and dare you to move them." (

25)

Helen told a story about how a White hair stylist treated another Turkish teenager. "This girl was dark, and she was a friend of mine. She said, 'I'd like to get my hair cut.' I said, 'There's a beauty shop up the street.' She said, 'Well, call and make me an appointment.' We walked up to the beauty shop, and we walked in. The lady said, 'I'm ready. Come in. You can sit in that chair.' I said, 'It's not for me. It's for her.' She said, 'Oh I can't cut her hair.' And she didn't." (

26)

Jean told this story. "One night, when the KKK was on the rampage, somebody burned a cross in my dad's yard. We got up the next morning and there was a cross burning in our yard; and for about two weeks, a lot of people stood guard out there. That was when the KKK was in full swing. I was terribly upset and afraid because you know what the KKK was doing. It was just kind of dreadful. We were scared. We were afraid to go outside the house." (

27)

All four denied that they were Native Americans; and their attitudes varied from puzzlement to indignation at the notion of Indian descent. Interestingly, too, they had little to say and spoke nothing negative about their relations with Black people.

In wrapping up the interviews, the respondents explained why they finally have spoken out about their reclusive community. Boaz stated: "I think it's good for some of those who have their ideas so to speak about the 'Turks' to understand our feelings. We're proud of who we are." Jean said she hopes to tell the story of the "Turkish people and their experience." Helen said she wants to tell about "the injustices that the Turkish people endured." Tonie put it very simply and pointedly: "I think the world needs to know what happened back then." (

28)

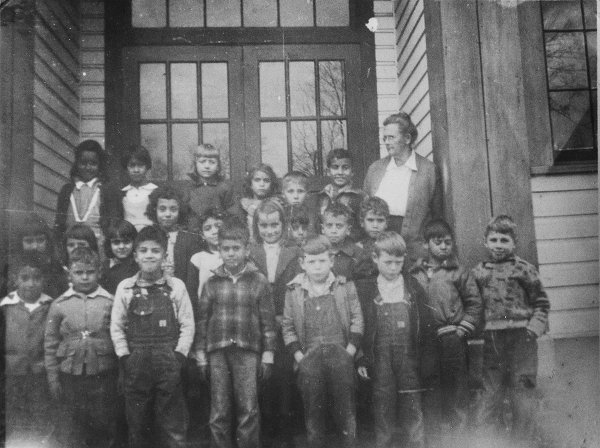

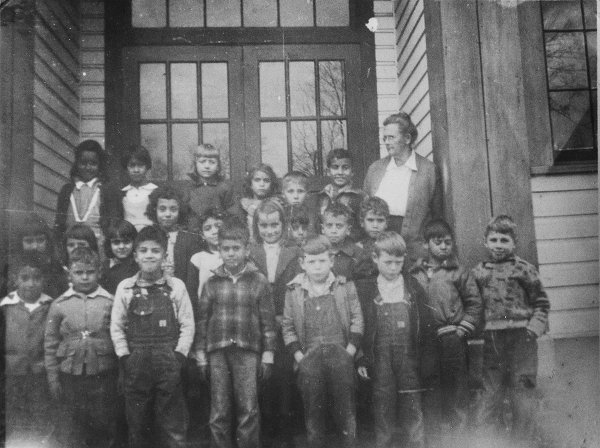

Students and their teacher at the Dalzell School, circa 1930s

[Provided by Glen Browder, PhD; Courtesy of the Greg Thompson Collection]

The Turkish People Today

Today, South Carolina's Turkish people (who prefer to be called "the Turkish people" rather than "the Turks") are not as enclosed as in the past and life is better for them. Most now marry outsiders. Many have moved to other areas, either to start a family or to attend college and begin careers. (

29)

The Turkish people also say that, generally, they are "treated right" in Sumter County of the twenty-first century. (

30) Attorney Brian Benenhaley, for example – a great-great-great-great-great grandson of the community patriarch – says that no one calls him a "Turk" anymore; he's "just a white guy with a long last name who gets a dark tan in the summertime." (

31) Just as importantly, he said, recent research will at least help him explain to his children who they are. "There's also some pride there, because it affirms that Joseph Benenhaley, or Yusuf ben Ali, served admirably at an important time in our nation's history, and made a contribution." (

32)

In simple terms, the research presented here is important because it tells, for the first time, the full and accurate history of this community. Now, the Turkish people understand and can celebrate their heritage.

Family and relatives of Noah Benenhaley (1860-1939). Noah was a grandson and his wife Rosa was a granddaughter of the patriarch. This photograph was taken at their farm home in 1903, Left to right: son, Jesse Noah/Noah Jr (1896-1960); father, Noah; his daughter Maybelle (1898-1972); his wife, Rosa Benenhaley (1857-1937); his nephew Joseph W Benenhaley (1882-1921); and his daughters Alberta (1886-1972), Florence (1882-1954), and Etta (1889-1961)

[Provided by Glen Browder, PhD; Courtesy of Greg Thompson Collection, donated to the collection by Isaac Benenhaley/David Peagler]

References

Wikramanayake, Marina. (1973) A World in the Shadows: The Free Black in Antebellum South Carolina (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina) p. 20.

Sass, Herbert Ravenel. (1956) The Story of the South Carolina Lowcountry, Vol. 1 (West Columbia, SC: J.F. Hyer Publishing Co.) p. 82.

"South Carolina's Raceless People" (1957) Ebony Magazine, pp. 53-56.

"Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School District No. 2, Sumter County, South Carolina."" Civil Action No. 3880. 1953; "Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School District No. 2, Sumter County, South Carolina." 232 F.2d 626. Case No. 7163. 1956; "Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School District No. 2, Sumter County, South Carolina." 286 F.2d 236. Case No. 8221, 1961; "Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School District No. 2, Sumter County, South Carolina." 295 F.2d 390. Case No. 8383. 1961.

See, for example, Bull, F. Kinloch. Random Recollections of a Long Life, 1896-1986. Unknown Binding, estimated 1986; located at South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina; Gregorie, Anne King. Thomas Sumter. Columbia, SC: R. L. Bryan Company, 1931; History of Sumter County, South Carolina. Sumter, SC: Library Board of Sumter County, 1954; Nicholes, Cassie. "County's 'Turk' Community Unique." Sumter News, Mar. 26, 1970; Historical Sketches of Sumter County: Its Birth and Growth. Sumter, SC: Sumter County Historical Commission, 1975; Sumter, Thomas Sebastian. "An Interesting People: Origin of the Bennanhaly and Scott Families." Watchman and Southron, Sep. 15, 1917; Stateburg and Its People. n.p.; probably published ca. 1920 in Stateburg or Sumter, SC.

Beale, Calvin L. "American Tri-Racial Isolates: Their Status and Pertinence to Genetic Research." Eugenics Quarterly 4, no. 4 (Dec. 1957): 187-96; –. "An Overview of the Phenomenon of Tri-Racial Isolates in the United States." American Anthropologist 74 (1972): 704-10; Gilbert, William Harlen, Jr. "Memorandum Concerning the Characteristics of the Larger Mixed-Blood Racial Islands of the Eastern United States." Social Forces 21, no. 4 (May 1946): 438-77; –. "Surviving Indian Groups of the Eastern United States," in Smithsonian Report for 1948. Government Printing Office, 1949: 407-38; Pollitzer, William S. "The Physical Anthropology and Genetics of Marginal People of the Southeastern United States." American Anthropologist 74, no. 3 (June 1972): 719-34; Price, Edward T. "A Geographic Analysis of White-Negro-Indian Racial Mixtures in Eastern United States." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 43 (June 1953): 138-55.

Berry, Brewton. "The Mestizos of South Carolina." American Journal of Sociology 51, no. 1 (1945): 34-41: –. Almost White. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1963; Diouf, Sylviane A. Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas. New York: New York University Press, 1998; Taylor, Rosser H. Ante-Bellum South Carolina: A Social and Cultural History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1942; Trillin, Calvin. "Sumter County, SC. Turks." New Yorker, Mar. 8, 1969, 104-10.

"Sumter County Colony Locally Called Turks," The State, March 18, 1928.

"Pockets in America," Federal Writers' Project, late 1930s.

Hill, S. Pony. Strangers in Their Own Land: South Carolina's State Indian Tribes. Palm Coast, FL: Backintyme, 2010.

Benenhaley, Eleazer. An Analysis of Neophytes and Would Be Historians. Belvedere, SC: Quality Printing, 2008, p. 37.

Ognibene, Terri Ann, and Glen Browder. South Carolina's Turkish People: A History and Ethnology (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 2018); and Glen Browder, "A Critical Analysis of the Sumter Cheraw Indian Tribe's Appropriation of the Turkish People's History: New Research Has Discredited Cultural Appropriation and Helped Correct the Official Record of Sumter County Ethnohistory (Sumter County Genealogical Society; February 17, 2020).

Sumter County, SC, Office of Mesne Conveyances (Deed Book DD, pp. 35, 36).

Sumter County, SC, Probate Court (Bundle 171, pkg 30).

"Thompson Collection and Interviews." Extensive Material.

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

White, Wesley, Jr. A History of the Turks Who Live in Sumter County, South Carolina, from 1805 to 1972. Unpublished manuscript, 1975, Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Ognibene and Browder

Richard Fausset, "Tracing the Roots of South Carolina's 'Turks,' Before They Melt Away," The New York Times, July 5, 2018.

Fausset, "Tracing the Roots of South Carolina's 'Turks,'" July 5, 2018.

Further Reading

- al-Ahart El, Muhammed. "Early American Settlers 1500-1850." Accessed Aug. 8, 2015.

- Baker, Robert. "Long Branch Marks 100 Years." Sumter Item, Oct. 30, 2004.

- Benenhaley, Eleazer. Moulded Clay. Orlando, FL: Daniels Printing Co., 1983; An Analysis of Neophytes and Would Be Historians. Belvedere, SC: Quality Printing, 2008.

- Berry, Brewton. "The Mestizos of South Carolina." American Journal of Sociology 51, no. 1 (1945): 34-41; Almost White. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1963.

- Browder, Glen. "A Critical Analysis of the Sumter Cheraw Indian Tribe's Appropriation of the Turkish People's History: New Research Has Discredited Cultural Appropriation and

Helped Correct the Official Record of Sumter County Ethnohistory (Sumter County

Genealogical Society; February 17, 2020).

- Browder, Glen, and Terri Ann Ognibene. "Solving the Two-Hundred-Year-Old Mystery of South Carolina's Turkish People," presented at the annual conference of the South Carolina Historical Association, Columbia, SC. March 10, 2018.

- Browder, Glen, and Terri Ann Ognibene. "Who Was Joseph Benenhaley? Exploring the 200-Year-Old Mystery of Sumter County's Turkish Patriarch and His People;" Carologue, (Fall-Winter, 2017).

- Bull, F. Kinloch. Random Recollections of a Long Life, 1896-1986. Unknown Binding, estimated 1986: located at South Caroliniana Library (Columbia, SC). "Carolina 'Turks' Lose School Plea," New York Times, October 6, 1956.

- Curtis, Edward E., IV. Muslims in America: A Short History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- "Ellison Family Papers." South Caroliniana Library. University of South Carolina.

- Ertan, Sevgi Zubeyde. "A History of Turks in America." 2002. Accessed Feb. 11, 2014 (previously online at: http://kucukcoban.8m.com/YAZILAR/turks_america.html).

- Fausset, Richard. "Tracing the Roots of South Carolina's 'Turks,' Before They Melt Away," The New York Times, July 5, 2018.

- Federal Writers' Project. "Pockets in America: The Turks in Sumter County, South Carolina." Ca. late 1930s; Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- "Furman Papers." Documents of Charles James McDonald Furman, at South Caroliniana Library. University of South Carolina.

- Gilbert, William Harlen, Jr. "Memorandum Concerning the Characteristics of the Larger Mixed-Blood Racial Islands of the Eastern United States." Social Forces 21, no. 4 (May 1946): 438-77; "Surviving Indian Groups of the Eastern United States," in Smithsonian Report for 1948. Government Printing Office, 1949: 407-38.

- Golden, Harry. Mr. Kennedy and the Negroes. Cleveland, OH: World Publishing Company, 1964.

- Gomez, Michael A. Black Crescent: e Experience and Legacy of African Muslims in the Americas. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Gregorie, Anne King. Thomas Sumter. Columbia, SC: R. L. Bryan Company, 1931; History of Sumter County, South Carolina. Sumter, SC: Library Board of Sumter County, 1954.

- Hagy, James W. "Muslim Slaves, Abducted Moors, African Jews, Misnamed Turks, and an Asiatic Greek Lady: Some Examples of Non-European Religious & Ethnic Diversity in South Carolina Prior to 1861." Carologue 9 (Spring 1993): 12-27.

- Hill, S. Pony. Strangers in Their Own Land: South Carolina's State Indian Tribes. Palm Coast, FL: Backintyme, 2010.

- Hilton, Johnny. "These People Don't Know Who I Am." Accessed May 29, 2014.

- Jewish Heritage Collection. "Oral History Interview with Ira Kaye and Ruth Barnes Kaye." June 15, 1996. Accessed Jan. 14, 2014 (previously online at: http://lowcountrydigital.library.cofc.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/JOH&CI

SOPTR=631&CISOBOX=1&REC=16).

- Johnson, Michael P., and James L. Roark. Black Masters: A Free Family of Color in the Old South. New York: W. W. Norton, 1984; No Chariot Let Down: Charleston's Free People of Color on the Eve of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Kaye, Ira. "The Turks: Alice in Sumterland." New South (June 1963): 9-15.

- Macron, Mary Haddad. "Arab Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland" (1979). Cleveland Memory. Book 22. Accessed Jan. 14, 2016.

- McElveen, W. A. "Bubba." "Our Town: Tuomey Changes Alter Downtown through the Years." Sumter Item, July 4, 1996.

- Mitchell, J.H. "Long Branch Church in the Santee." Baptist Courier. Apr. 1, 1943.

- Moore, Ivy. "Authors of book on Sumter's Turkish people to give presentation at museum." Sumter Item, Apr. 1, 2018.

- Muhammad, Amir Nashid Ali. Muslims in America: Seven Centuries of History (1312-2000). Beltsville, MD: Amani Publications, 2001.

- Myers, Portia. "Our 'Turk' Community Is One of a Kind." Sumter Item, Aug. 5, 1989.

- New, Sue. "Joseph Being Called Yusef Ben Ali Was First recorded by Thomas Sumter's Grandson." 2005. Accessed July 17, 2005.

"Benenhaley, or a Story of the 'Turks' of Sumter County." 2002-2010. Accessed Nov. 15, 2013.

"Census Data for the 'Turks' of Sumter County." 2002-2005. Accessed Feb. 21, 2014.

- Nicholes, Cassie. "County's 'Turk' Community Unique." Sumter News, Mar. 26, 1970; Historical Sketches of Sumter County: Its Birth and Growth. Sumter, SC: Sumter County Historical Commission, 1975.

- Ognibene, Terri Ann. "Discovering the Voices of the Segregated: An Oral History of the Educational Experiences of the Turkish People of Sumter County, South Carolina." PhD Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008.

- Ognibene, Terri Ann, and Glen Browder. South Carolina's Turkish People: A History and Ethnology. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 2018.

- Pollitzer, William S. "The Physical Anthropology and Genetics of Marginal People of the Southeastern United States." American Anthropologist 74, no. 3 (June 1972): 719-34.

- Price, Edward T. "A Geographic Analysis of White-Negro-Indian Racial Mixtures in Eastern United States." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 43 (June 1953): 138-55.

- Ray, Celeste. The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Ethnicity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

- Sass, Herbert Ravenel. (1956). The Story of the South Carolina Lowcountry, Vol. 1. West Columbia, SC: J.F. Hyer Publishing Co., p. 82.

- "S.C. 'Turks' To Attack School Law," The State, January 10, 1951.

- "South Carolina Colony of 'Turks,'" Lubbock Evening Journal, September 9, 1953.

- "South Carolina's Raceless People," 1957, pp. 53-56. Ebony Magazine.

- Stockbridge, Kay M. Presentation on the "Turks" of Sumter County, at the Sumter County Museum, Sumter, SC. 1995.

- "Sumter County Colony Locally Called Turks." The State, March 18, 1928.

- Taukchiray, Wesley DuRant, and Alice Bee Kasakoff. "Contemporary Native Americans in

South Carolina," in Indians of the Southeastern United States in the Late 20th Century, edited by Anthony J. Paredes, 72-99. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1992.

- Thompson Collection and Interviews. Documents, photographs, conversations shared by Greg Thompson with the authors during the writing of this book.

- Thompson, Greg. "Turks Can Be Traced Back to Thomas Sumter." Sumter Item, Progress 2000, April 2000.

- "Timmerman Refuses Sumter Turk Appeal." Sumter Daily Item, December 2, 1955.

- Trillin, Calvin. "Sumter County, SC. Turks." New Yorker, March 8, 1969, 104-10.

- "'Turk' Case Is Closed," Sumter Daily Item, February 15, 1961.

- "Turkish Children No Longer Segregated, Thanks to the NAACP," Pittsburgh Courier, March 4, 1961.

- "Turks Lose Ground on Grammar School." Sumter Daily Item, May 29, 1956.

- "'Turks' Seeking Educational Opportunities," News and Courier, December 17, 1950.

- "Turks Win School Battle," Charlotte Observer, February 15, 1961.

- US Air Force, Air Combat Command. "Archaeological Resources Overview of Shaw Air Force

Base and Poinsett Electronic Combat Range." April 2006. Accessed November 15, 2013 (previously online at: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a453315.pdf).

- White, Wesley Jr. A History of the Turks Who Live in Sumter County, South Carolina, from 1805 to 1972. Unpublished manuscript, 1975, Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

- Wikramanayake, Marina. A World in the Shadows: The Free Black in Antebellum South Carolina. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 1973, p. 20.

- Workman, William D. Jr. "Sumter County 'Turks' Are Old Inhabitants," News and Courier, Charleston, SC, Dec. 16, 1950; "'Turks' Seeking Educational Opportunities for Children," News and Courier, Charleston, SC, Dec. 17, 1950; "Old Legislative Petition May be Clue to Identity of Sumter County 'Turks,'" News and Courier, Charleston, SC, Feb. 12, 1951; "Sumter 'Turks' Descendants of Men Who Served in American Revolution," News and Courier, Charleston, SC, Sept. 10, 1953; "Sumter 'Turks' Stem from Early Soldiers," News and Courier, Charleston, SC, Sept. 10, 1953.