Mitchelville After the Civil War

South Carolina

In 1865 the Civil War was over and Hilton Head had lost its strategic importance. When the military abandoned the island in January 1868, so too did the jobs. While a great deal of thought had gone into the establishment of Mitchelville, no one bothered to wonder how the village would survive without the wage labor of the military. It was probably unthinkable to them that the land on which Mitchelville was situated would ever be returned to its white owners.

In spite of these changes, it appears that Mitchelville was still an active village. An AMA teacher described Mitchelville in 1867:

"[t]here are several large plantations upon which are small settlements, but the greater part of the colored population of the island are located a short distance from Hilton Head [meaning the old military base] at a place called Mitchelville. . . . It is an incorporated town, regularly laid out in streets and squares. About 1500 inhabitants, not a single white person. There are three churches - two Baptist, one Methodist, two schools which are taught by A.M.A. teachers."There were no whites living in Mitchelville since "The Home," where AMA teachers had previously lived, had blown down during a storm in November 1867. What remained of the building, however, was still being used as a school.

Although the military had left, taking jobs with them, many blacks turned to subsistence farming. Some formed "collectives," joining together to rent large plantations from the government. Many of the freedmen were able to save their wages until they had the money to purchase land. However, there was a gathering storm in Washington. Congress passed laws providing for the restoration of confiscated lands to Southern owners with the payment of taxes, costs, and interests. Many of the lands being planted by the freedmen were no longer available. Worse, many lands purchased by freedmen in good faith, were returned to their Southern owners, with the blacks divested of their interest.

The Drayton Plantation (on which Mitchelville was located) was returned to the heirs of its former owner in April 1875, with the federal government deed failing to provide any protection for Mitchelville. The Drayton heirs, however, were not interested in planting the lands and began to sell it off to anyone interested in making purchases - including many freedmen. It was during the last quarter of the nineteenth century that most, if not all, of Mitchelville was purchased by a black man, March Gardner. March, while illiterate, was very successful - and apparently well respected. He placed his son, Gabriel, in charge of Mitchelville, which at this time also included a store, cotton gin, and grist mill. March also trusted Gabriel to have a proper deed made out. Instead, Gabriel took advantage of his father, eventually obtaining a deed in his own name and then transferring the property to his wife and daughter.

In the early twentieth century, the heirs of March Gardner took the heirs of Gabriel Gardner's wife to court, claiming they owned what was left of Mitchelville and that Gabriel Gardner had stolen the property. Although this is a sad end to what was the birthplace of freedom for many Sea Island blacks, the court case does help us understand the village better during this period, since the court took extensive statements from people living in the village.

The daughter of March Gardner, Emmeline Washington, testified that a number of families were living at Mitchelville and farming three or four acre plots adjacent to their houses. The money that was collected for rent went to pay the taxes on the property. March Gardner, who was by trade a carpenter, had built a cotton gin, cotton house (for storing the cotton), and steam powered grist mill on the property while it was still a village. He also built a shop on one of the Mitchelville roads, apparently near his own house, where he planted peas and cotton.

The court papers also name a number of the Mitchelville residents during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries - John Nesbit, Bob Washington, Caesar White, Charles Robins, Charles Perry, Robert Wiley, Scapio Drayton, Jack Screven, Charles Pinckney, Billy Reed, Peter Flowers, Joe Williams, Hannah Williams, Stephen Singleton, Linda Perry, Renty Miller, and Clara Wigfall. One resident, Hannah Williams, explained how she had purchased a house in Mitchelville for $5.

A number of individuals saw in Mitchelville an opportunity to make money. With the federal government leaving Hilton Head, and the blacks relatively illiterate, it was perhaps easy enough for Drayton's heirs to sell Mitchelville twice - first to March Gardner, and then, again, to his son, Gabriel Gardner. Mitchelville was not situated on prime agricultural land and the Draytons probably felt (correctly, it seems) that few planters would want to purchase a black town. March, and later his son Gabriel, however, began collecting rents on (and selling) property other blacks had been using for years. The town functioned, essentially, as a collective, tying all of the parties together. It is likely that many of those living in Mitchelville had done so for several decades.

The court directed that a survey be made and the property of Mitchelville be divided among the heirs upon each paying their share of the costs associated with the case. Eugenia Heyward redeemed her tract of 35 acres on June 7, 1923. Celia and Gabriel Boston obtain the adjacent tract on September 2, 1921. Linda Perry, Emmeline Washington, and Clara Wigfall also obtained their respective parcels in 1921.

By 1930 the 35-acre Eugenia Heyward tract was sold for $31.00 by the Sheriff to pay a defaulted tax bill of $15.00. The purchaser was Roy A. Rainey of New York, who was purchasing much of the island for exclusive hunting. As more and more of Hilton Head Island was sold, the black population was reduced from the nearly 3,000 on the island in 1890 to only about 300 in the late 1930s.

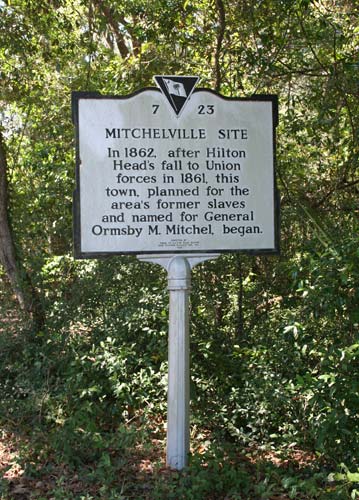

MITCHELVILLE

An Experiment in Freedom

Evolution of Mitchelville

Mitchelville After the Civil War

Archaeological Study of Mitchelville

Can Mitchelville Be Preserved?

More Information

The Chicora Foundation

CHICORA FOUNDATION ARTICLES

Understanding Slavery

Free Blacks in Charleston

Preserving Black Cemeteries

Mitchelville Experiment

Quash Stevens Letters